NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The Spy Ship Left Out in the Cold

A half-century after one of history’s most controversial attacks on a U.S. Navy ship, the wounds from the Liberty incident remain unhealed.

by James M. Scott

June 2017

Naval History Magazine

Volume 31, Number 3

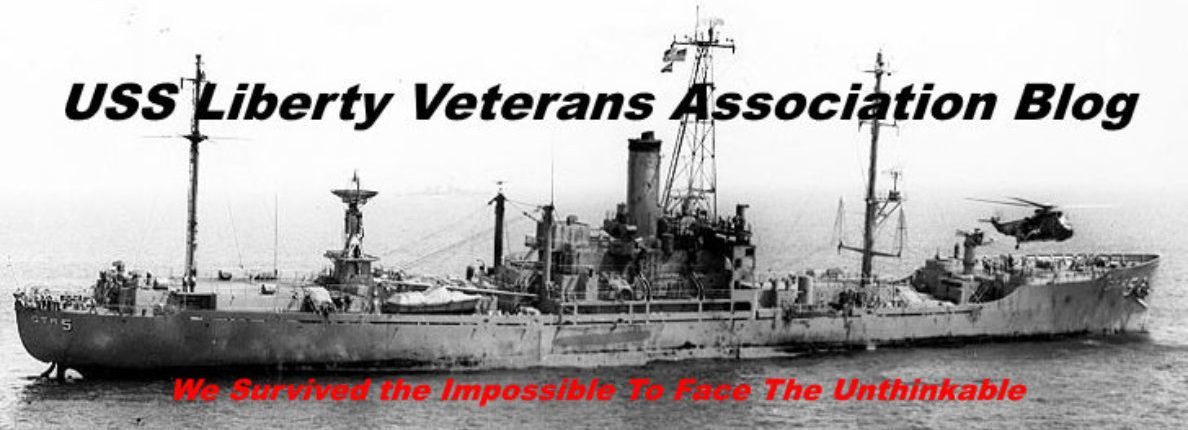

The 8th of June this year will mark the 50th anniversary of the attack on the USS Liberty (AGTR-5), a spy ship the Israelis repeatedly strafed, napalmed, and torpedoed during a ferocious hour-long assault that The Washington Post later described as “one of the most bloody and bizarre peacetime encounters in U.S. naval history.”((Michael E. Ruane, “An Ambushed Crew Salutes Its Captain,” The Washington Post, 10 April 1999.))

In the five decades since that tragic afternoon on which 34 Americans were killed and another 171 wounded, the Liberty has become an albatross.

The long-standing pleas of surviving crew members—convinced Israel intentionally targeted the ship—for a congressional investigation have fallen on deaf ears. Lawmakers never have—nor likely ever will—pick up a cause that even a half-century later remains so politically fraught that midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy were barred from even asking questions about it during a 2012 visit by the Israeli ambassador.((Thomas E. Ricks, “Was There Academic Freedom at Annapolis During the Israeli Ambassador’s Visit?” Foreign Policy, 23 January, 2012.))

But the story of the unprovoked attack on a U.S. ship in international waters still ignites passions, not only among the survivors, whose numbers are dwindling, but also among authors, filmmakers, and the legions of online sleuths whose zealousness has prompted Wikipedia to lock down the editing page on the assault.

All this comes at a time when declassified documents in the United States and Israel, coupled with interviews of those involved, help illustrate what a sordid affair the Liberty was for both nations. Records show, for example, that U.S. leaders, anxious to protect Israel from the public-relations fallout, went so far as to contemplate sinking the ship at sea to prevent reporters from photographing the damage. Israeli diplomats meanwhile manipulated the media to downplay or kill stories about the attack and even silenced an angry President Lyndon Johnson by threatening to publicly accuse him of “blood libel” or anti-Semitism.

Senior naval officers, following the lead of U.S. politicians, refused to thoroughly investigate the attack. “The Navy was ordered to hush this up, say nothing, allow the sailors to say nothing,” said Rear Admiral Thomas Brooks, a former Director of Naval Intelligence. “The Navy rolled over and played dead.”((Thomas Brooks, interview with author, 21 February 2007.))

None of this was known by the public at the time, a fact some senior leaders later regretted, recognizing that the lack of accountability served as the catalyst for the controversy that still haunts the Liberty decades after metal cutters reduced her to scrap in a Baltimore shipyard. “We failed to let it all come out publicly at the time,” recalled Lucius Battle, who served as the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs. “We ignored it for all practical purposes, and we shouldn’t have.”((Lucius Battle, interview outtake, documentary Dead in the Water, Christopher Mitchell, director, Source Films for BBC, 2002.))

From Calm to Inferno

The Liberty was part of a secret program run by the U.S. Navy and the National Security Agency (NSA) in which the United States dispatched cargo ships outfitted as mobile listening platforms to eavesdrop on the world’s hot spots—places such as Cuba, North Korea, and the Middle East. Though the Liberty officially was classified as a technical research ship, her 45 towering antennas used to soak up communications of foreign nations made it obvious to any trained observer that she was a spy ship.

The vessel was armed with only four .50-caliber machine guns to repel boarders; her principal defense rested on the idea that no nation would dare attack a U.S.-flagged vessel in international waters. That flawed logic was exposed, not only with the attack on the Liberty, but also with North Korea’s seizure just seven months later of the spy ship Pueblo (AGER-2). The Liberty’s principal operating area was West Africa, but in late May 1967, as tensions mounted between Israel and its Arab neighbors, the ship received orders to depart immediately for the eastern Mediterranean to monitor what we now know as the Six-Day War.

At 0515 on 8 June—soon after the Liberty arrived off the coast of the Sinai Peninsula—the first Israeli reconnaissance plane circled the ship several times. That initial recon flight on the morning of the war’s fourth day began a steady pattern of observation that continued for hours. A State Department report later determined that recon planes buzzed the Liberty as many as eight times over a nine-hour period. Some planes flew so low that crewmen on deck could see the pilots. Sailors took confidence in the fact that the Liberty steamed in international waters and was clearly marked with freshly painted hull numbers on her bow and her name stenciled across the stern. Visibility was excellent. The U.S. flag fluttered from the mast.

But that calm was shattered at 1358 when Israeli fighters suddenly strafed the Liberty from bow to stern with rockets and cannon fire. Fighters crisscrossed the spy ship nearly every minute, targeting the machine-gun tubs, antennas, and the bridge. The aircraft also blasted the sides of the ship in an effort disable the engine room. Liberty radiomen, desperate to alert the 6th Fleet approximately 500 miles west near Crete, found their communications jammed. A second wave of fighter-bombers dropped napalm, turning the Liberty’s decks into a 3,000-degree inferno.

Three torpedo boats attacked at 1431, strafing the ship with cannon fire and .50-caliber machine guns firing armor-piercing rounds. In a cruel twist of fate, investigators later determined that some of the munitions were U.S.-made. At 1435, a torpedo hit the starboard side of the ship, killing more than two dozen men. The Liberty rolled nine degrees as water flooded her lower compartments. Generators shut down, power went out, and the steering failed as the ship became dead in the water. The torpedo boats then continued to strafe the ship. Armor-piercing bullets zinged through bulkheads, shattered coffee mugs, and lodged in navigation books. Others shredded several life rafts Liberty sailors had dropped in the water.

The brutal assault left 34 men dead and 171 wounded—two out of every three men on board were either killed or injured. In addition to the torpedo hole, which measured 24 feet tall by 39 feet wide, naval investigators later counted 821 shell holes, a figure that did not include machine-gun rounds and shrapnel holes, which were deemed simply “innumerable.” The 67-minute attack would prove to be the bloodiest assault on a U.S. ship since World War II, one best described by Patrick O’Malley, a Liberty ensign at the time. “There wasn’t any place that was safe,” he recalled. “If it was your day to get hit, you were going to get hit.”((Patrick O’Malley, interview with author, 26 November 2007.))

Accident? ‘Inconceivable’

Back in Washington, President Johnson and his advisers gathered in the Situation Room the morning of the attack. While relieved neither Egypt nor the Soviets were responsible, Johnson and his team realized that an attack by Israel—an ally with a loyal domestic following—raised a host of other complicated political issues for the administration. At the time, the United States was bogged down by the Vietnam War, where 26 men died each day in 1967. In May, that number spiked to 38 men a day. Johnson’s approval numbers simultaneously were plummeting from 61 percent in March 1966 to just 39 percent in August 1967. It all came down to Vietnam.

Complicating matters, American Jews—a powerful and important constituency for Johnson, who was facing reelection in 1968—were at the forefront of the antiwar movement. Adding to his frustration was the fact that he had done more than any prior President to improve U.S.-Israeli relations. “If Viet Nam persists,” one memo warned him, “a special effort to hold the Jewish vote will be necessary.”((“1968—American Jewry and Israel,” undated, Box 141, National Security File, Country File, Israel, Lyndon B. Johnson Library, Austin, TX (hereafter LBJL).))

The Liberty—riddled with cannon blasts, her decks soaked in blood, her starboard side ripped open by a torpedo—evolved in a matter of hours from a top-secret intelligence asset to a domestic political liability. That was evident by one proposal. “Consideration was being given by some unnamed Washington authorities to sink the Liberty in order that newspaper men would be unable to photograph her and thus inflame public opinion against the Israelis,” NSA Deputy Director Louis Tordella wrote in memo for the record. “I made an impolite comment about that idea.”((Louis W. Tordella, Memorandum for the Record, 8 June 1967, National Security Agency (hereafter NSA).))

The day after the attack, Johnson met with his Special Committee of the National Security Council. The Liberty discussion was heated, minutes show, as Johnson’s advisers spurned Israel’s claim that the attack was simply a tragic accident. Clark Clifford, head of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board and one of Johnson’s most pro-Israel advisers, demanded the attackers be punished. “Inconceivable that it was an accident,” Clifford said. “Punish Israelis responsible.”((Meeting Minutes of the Special Committee of the National Security Council, 9 June 1967, Box 19, National Security File, National Security Council Histories, Middle East Crisis, LBJL.))

Clifford’s strong comments—echoed by others in the meeting, including the President—reflected just how upset many in Washington were over the attack, a hostility that was never shared with the American public.

To senior officials, the idea that the attack on the Liberty was friendly fire defied logic. Friendly fire accidents often happen at night or in bad weather. Furthermore, such accidents tend to be over in a matter of seconds, maybe minutes.

In contrast, the attack on the Liberty occurred on a clear, sunny afternoon in international waters. No other ships were in the area. The attack involved two branches of Israel’s vaunted military and raged for approximately an hour.

In the heat of battle, Liberty officers were able to identity the flag and hull number off a swift-moving torpedo boat, yet Israel claimed its own forces were unable to identify a lumbering cargo ship with towering hull numbers, her name on the stern and an American flag on the mast. To many, that seemed impossible. “I just don’t believe that it was an accident or trigger happy local commanders,” Secretary of State Dean Rusk later said. “There was just too much of a sustained effort to disable and sink the Liberty.”((Dean Rusk, undated oral history with Richard Geary Rusk and Thomas J. Schoenbaum, Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia.))

But it wasn’t just politicians who disputed Israel’s explanation. Senior intelligence leaders also were convinced the attack was no accident. “It couldn’t be anything else but deliberate,” concluded NSA Director Marshall Carter. “I don’t think there can be any doubt that the Israelis knew exactly what they were doing,” recalled CIA Director Richard Helms. “We were all quite convinced the Israelis knew what they were doing,” added Thomas Hughes, director of the State Department’s intelligence bureau.((Marshall S. Carter, oral history with Robert D. Farley, 3 October 1988, NSA. Richard Helms, oral history with Robert M. Hathaway, 8 November 1984, Central Intelligence Agency (hereafter CIA). Thomas Hughes, interview with author, 26 April 2007.))

Many senior Navy officers agreed. Vice Admiral Jerome King, senior aide to Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral David McDonald, challenged the claim of friendly fire. “It certainly was not mistaken identity,” he later said. “I don’t buy it. I never did. Nobody that I knew ever did either. It wasn’t as though it was at night or a rainy day or anything like that. There wasn’t any excuse for not knowing what that ship was. You could divine from just the apparatus on deck—all the antennae and so on—what its mission was.”((Jerome King Jr., interview with author, 6 February 2008.))

‘Wonderful. She’s Burning!’

So how did Israeli pilots fail to identify the Liberty? How, over multiple strafing runs and often at low altitudes, had no pilot noticed the spy ship’s unique markings, particularly considering Egyptian ships are marked in Arabic script, not Western letters?

Transcripts of Israeli communications, which have become available in recent years, show that the case is not as simple as the Israeli government wanted the United States to believe in 1967. Two minutes before the strafing began, an Israeli weapons system officer in general headquarters blurted out: “What is it? Americans?”((Transcripts of the attack come from Ahron Bregman, Israel’s Wars: A History Since 1947 (New York: Routledge, 2002), 88–90; and Arieh O’Sullivan, “Liberty Revisited: The Attack,” Jerusalem Post, 4 June 2004, 20.))

Despite the doubts raised about the ship’s identity, Israel’s chief air controller, Shmuel Kislev, neither halted the impending assault nor ordered pilots to inspect the ship for identifying markings or a flag as their fighters zeroed in on the Liberty.

“Great! Wonderful. She’s burning! She’s burning!” transcripts show one of the pilots exclaimed during the attack.

“Authorized to sink her?” one of the air controllers asked.

“You can sink her,” replied Kislev.

A pilot joked at one point during the strafing runs that hitting the defenseless ship was easier than shooting down MiGs. Another quipped that it would be a “mitzva”—a kind deed or blessing—to sink the Liberty before Israeli ships arrived.

“Is he screwing her?” Kislev asked at one point.

“He’s going down on her with napalm all the time,” replied another controller.

Shortly before the planes exhausted all their ammunition, Kislev finally asked the pilots to look for a flag. One of the pilots buzzed the ship moments later and spotted the Liberty’s hull number. He radioed it to ground control, albeit one letter off.

“What country?” asked one of the air controllers.

“Probably American,” Kislev replied.

“What?”

“Probably American.”

“At that point in time, in my mind, it was an American ship,” Kislev later admitted. “I was sure it was an American ship.”((Attack on the Liberty, directed by Rex Bloomstein, Thames Television, 1987.))

Israel had conclusively identified the Liberty as much as 26 minutes before the fatal torpedo strike. According to Israeli documents, the pilot’s report was passed to the Israeli Navy, where the vice chief of naval operations dismissed it as camouflage writing to allow an Egyptian ship to enter the area. Israeli documents likewise show that at least two other Israeli naval officers suspected that before the torpedo attack, the target was none other than the Liberty. Neither intervened to halt the attack.

On board the Liberty at that time, far belowdecks, frantic sailors burned classified papers, bagged magnetic tapes, and destroyed key cards until word was passed to stand by for a torpedo attack. The men tucked their pants legs into their socks and buttoned up their shirts to protect against flash burns. Many prayed. One man, who did not want to see what was about to happen, took off his glasses and slipped them in his shirt pocket. At 1435, the torpedo struck and in a flash killed 25 men.

Media Spin Begins

Israeli Ambassador Avraham Harman wrote to his superiors in Jerusalem that he believed that several parties were guilty of negligence. Harman demanded that Israel prosecute the attackers. He even suggested that American journalists be invited to cover the trial. “In the severe situation created,” he cabled Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, “the only way to soften the results is if we could let the US Government know already today that we intend to prosecute people in connection with this disaster.”((Avraham Harman, telegram 305 to the Foreign Ministry, 19 June 1969, 4079/HZ-26, Israel State Archives (hereafter ISA).))

But Harman’s demands were soon overshadowed by the political tug-of-war that erupted between Israel and the United States. Secretary of State Rusk sent a stinging letter to Israel’s ambassador, describing the assault as “quite literally incomprehensible” and arguing that it represented “wanton disregard for human life.” Rusk demanded that Israel punish the attackers in accordance with international law.((Dean Rusk, letter to Avraham Harman, 10 June 1967, Box 107 (2 of 2), National Security File, Country File, Middle East, LBJL.))

Israeli diplomats feared the United States planned to use the attack as a political tool to dampen the U.S. public’s enthusiasm for Israel, dangerous ground for the Jewish state as it prepared to negotiate a peace deal that would involve controversial issues such as territorial gains and refugees. Israel decided to fight back, launching a political and media spin campaign. “Our informative process,” one cable stated, “must avoid confrontation with the United States Government, since it is clear that the American public, if faced with a direct argument, will accept its government’s version.”((Ephraim Evron, telegram 156 to the Foreign Ministry, 11 June 1967, 4079/HZ-26, ISA.))

Israeli diplomats tapped influential American Jews, many of whom were close friends with President Johnson, to help. Documents show that Eugene Rostow, who was third in command of the State Department, repeatedly shared privileged information about U.S. strategy with Israeli diplomats. Others who assisted Israel included Supreme Court justice Abe Fortas and Arthur Goldberg, who was the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Many of these and others who helped the embassy are referred to by code names in Israeli documents. For example, Democratic fund-raiser Abe Feinberg is identified in Israeli records by the codename “Hamlet.”

Israeli diplomats likewise hammered the media to kill critical stories and slant others in favor of Israel. Diplomats hustled, for example, to derail a potential news story about pressure on New York Representative Otis Pike to launch a congressional investigation into the attack. “We have made sure that the journalistic source will refrain from writing about this for now,” cabled embassy spokesman Dan Patir.((Dan Patir, telegram 115 to the Foreign Ministry, 11 July 1967, 4079/HZ-26, ISA.))

The day after the attack, Johnson confided to a Newsweek reporter that he believed Israel deliberately attacked the Liberty to prevent her from spying. Israeli officials learned the details of Johnson’s interview within 24 hours and successfully pressured the magazine to water down its planned story. “The Newsweek editorial has made changes in the last proofreading of the news item compared with the original version that I was shown last night,” Patir cabled Jerusalem. “It toned down the version by adding a question mark to the heading, leaving out the words deliberate attack, and leaving out the commentary paragraph that said that the leak is intended to free American policy makers from the pressure of the pro-Israeli public opinion.”((Dan Patir, telegram 163 to the Foreign Ministry, 11 June 1967, 4079/HZ-26, ISA.))

Diplomats also needed to tone down President Johnson. To pressure the President, Israeli officials tapped Justice Fortas and Washington lawyer David Ginsburg to make Johnson “aware of the dangers facing him personally if the public learns that he was party to the distribution of the story that is on the verge of being blood libel.”((Ephraim Evron, telegram 156 to the Foreign Ministry, ISA.))

Fallout Prevention vs. Full Inquiry

Ultimately, Israeli diplomats succeeded in pressuring the administration. Johnson, whose focus largely was on Vietnam, looked for a compromise that would guarantee that American families were compensated but would not risk a clash with Israel’s domestic supporters. He ordered Nicholas Katzenbach, second-in-command at the State Department, to negotiate the deal: If Israel publicly apologized for the attack and paid reparations, the United States would let it go, no more questions asked.((Nicholas Katzenbach, interview with author, 19 April 2007.))

The administration’s decision not to dig into the Liberty incident was evident in the incredibly weak effort the Navy made to investigate the attack. “Shallow,” “cursory,” and “perfunctory” were words Liberty officers used to describe the court of inquiry, which spent only two days interviewing crew members in Malta for an investigation into an attack that had killed 34 men.((Author interviews with Lloyd Painter (13 April 2008), Mac Watson (23 April 2008), and John Scott (13 April 2008).)) The proceeding’s transcript shows just how shallow it truly was. The Liberty’s chief engineer was asked only 13 questions. A chief petty officer on deck during the assault and a good witness about the air attack was asked only 11 questions. Another officer was asked just 5 questions.

In evaluating the Liberty court of inquiry, it is worth comparing it to the court that examined North Korea’s capture of the Pueblo. The Liberty court lasted just eight days, interviewed only 14 crewmen, and produced a final transcript that was 158 pages. In contrast, the Pueblo court lasted almost four months, interviewed more than 100 witnesses, and produced a final transcript that was nearly 3,400 pages.

Captain Ward Boston, the lawyer for the Liberty court, broke his silence in 2002, stating that investigators were barred from traveling to Israel to interview the attackers, collect Israeli war logs, or review communications. Furthermore, he said Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had ordered the court to endorse Israel’s claim that the attack was an accident, which Boston personally did not believe was the case. “I am certain that the Israeli pilots that undertook the attack, as well as their superiors who had ordered the attack, were well aware that the ship was American.”((Ward Boston Jr., affidavit, 8 January 2004, a copy of which Representative John Conyers of Michigan inserted into the Congressional Record, 11 October 2004.))

In Washington, Deputy Defense Secretary Cyrus Vance oversaw the Pentagon’s effort to condense the court’s full report into a declassified summary that could be released to the press. This, too, needed to support Israel’s version of events and not raise questions. The overt effort by Vance’s office to protect Israel from the potential public-relations fallout angered senior Navy officers. CNO McDonald, after reading the draft prepared for the public, fired off an angry handwritten memo about it. “I think that much of this is extraneous and it leaves me with the feeling that we’re trying our best to excuse the attackers,” McDonald wrote. “Were I a parent of one of the deceased this release would burn me up. I myself do not subscribe to it.”((David L. McDonald’s Comments/Recommended Changes on Liberty Press Release, 22 June 1967, Box 112, Immediate Office files of the CNO, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington Navy Yard.))

Likewise, Vance clashed with NSA Director Carter over the Liberty, ordering him to keep his “mouth shut,” a demand that infuriated senior intelligence officials, such as NSA Chief of Staff Gerard Burke. “There was absolutely no question in anybody’s mind that the Israelis had done it deliberately,” Burke later said. “I was angrier because of the cover-up—if that’s possible—than of the incident itself, because there was no doubt in my mind that they did it right from the outset. That was no mystery. The only mystery to me was why was the thing being covered up.”((Gerard Burke, interview with author, 4 October 2007.))

‘A Nice Whitewash’

U.S. leaders had hoped Israel would punish the attackers, as both Dean Rusk and Israeli Ambassador Harman had demanded. In August, however, U.S. officials learned that the Israeli judge tasked to examine the attack instead had exonerated everyone. The assault on the Liberty, which had raged for approximately an hour on a clear afternoon in international waters, was the most violent attack on a U.S. naval ship since World War II. Yet Israel’s investigating judge could find no evidence of wrongdoing, no negligence, no violation of military procedure.

U.S. officials slammed that decision. “A nice whitewash for a group of ignorant, stupid and inept XXX,” Tordella wrote in a handwritten memo, substituting the letter X for an expletive. “If the attackers had not been Hebrew there would have been quite a commotion.”((Louis W. Tordella, handwritten note, 26 August 1967, NSA.)) Tordella’s memo reflected the special treatment many in Washington recognized Israel received in the aftermath of the attack. The failure to reprimand anyone left lingering resentment among many, including Vice Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Horacio Rivero, who was later asked for his most prominent memory of the Liberty: “My anger and frustration at our not punishing the attackers.”((Horacio Rivero Jr., Q&A with Joseph F. Bouchard, 10 March 1988.))

The administration’s effort to deemphasize the Liberty also spilled over into the presentation of awards in June 1968. Liberty skipper Commander William McGonagle was nominated for the Medal of Honor, an award customarily presented by the President at the White House. McGonagle would not be so lucky. The President’s senior military aide, James Cross, urged Johnson not to present McGonagle’s medal in person and to make sure the White House issued no press release. “Due to the nature and sensitivity of these awards, Defense and State officials recommend that both be returned to Defense for presentation, and that no press release regarding them be made by the White House.”((Jim Cross, memo to Lyndon Johnson, 15 May 1968, Box 17, White House Central Files, Medals-Awards, LBJL.))

In 1968, Israel paid $3.3 million to the families of the men killed. A year later, Israel paid $3.5 million to the men who were injured. Israel then balked at paying the $7.6 million for the loss of the ship, secretly offering at one point the token sum of $100,000. Negotiations dragged on until 1980, at which time the bill plus interest totaled more than $17 million. Under the threat of a congressional investigation, Israel struck a deal to pay $6 million in three annual installments. The United States accepted.

Even now, a half-century later, the attack on the Liberty and our government’s handling of the affair are still very much a painful part of many lives—including Chris Armstrong, the son of Liberty executive officer Philip Armstrong, who was killed that afternoon. Chris, who was three at the time, received $52,000 for the loss of his father. “It paid for my college education, but not much else,” he said. “I would give it all back and then some. My emotional scars are very deep from this incident.”((Chris Armstrong, email to author, 18 July 2009.))

James M. Scott is the author of Target Tokyo (W. W. Norton, 2015), which was a 2016 Pulitzer Prize finalist for history. He also is the author of The War Below (Simon & Shuster, 2013) and The Attack on the Liberty (Simon & Shuster, 2009), which was named one of 20 Notable Naval Books of 2009 by Proceedings and won the Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Excellence in Naval Literature. Scott’s father, John Scott, was a U.S. Navy ensign and damage control officer serving on board the Liberty during the attack. He received the Silver Star for his actions that day.